For decades, it was a routine occurrence for pregnant women to lose their jobs because of their bump or be forced to take early maternity leave with no guarantee they’d have a job upon return. Then, in the mid-1970s, a grassroots movement began to fight for pregnancy rights and change the status quo. Today, 50 years later, that movement has led to what we know as Paid Family and Medical Leave (PFML), a broader protection that cares for the whole family.

PFML benefits are intended to cover the realities of life for American workers – from the joy of bonding with a new child to the steady support often needed to care for aging, ailing parents. PFML recognizes that healing from setbacks or transitions, both physical and emotional, takes time.

Even before the dark days of COVID-19 cast a bright light on the need for this kind of paid leave, an increasing number of employers and states had been making PFML more accessible. They are solidifying this as a benefit that’s here to stay. It helps employers compete for top talent and care for today’s multi-generational workforce, especially as the U.S. economy picks up post-pandemic momentum.

Here are nine things about PFML – past, present and future – that you should know:

1. PFML Is Not Just for New Parents

PFML gives employees a cash benefit (usually a percentage of their income) when they take time off to care for themselves and/or family members. In general, the reasons for leave include:

- Bonding with a new child (through birth, adoption or foster placement)

- Recovering from a personal serious health condition (illness or injury)

- Caring for a family member with a serious health condition

- Attending to certain military-related events, such as pre- or post-deployment preparations

- Attending to the legal and/or medical needs for the employee or family members who are victims of violent crimes

2. Families Come In All Forms

What makes a family? Well, love for starters. Most states with a PFML program have expanded the definition beyond the immediate, nuclear family. Under a broader umbrella, and depending on the state, an employee could take PFML to care for in-laws, siblings, grandchildren, grandparents and people who may or may not be related by blood, but by whose close bonds are considered a family relationship.

3. Your Location Matters

There are more than a dozen states that require some form of paid family leave, paid medical leave or a combination of both. The reasons for leave are generally the same, but eligibility, cash benefits and the length of leave can vary from state to state. In fact, some states even call it by a different name. In Rhode Island, for example, the benefits are called “temporary caregiver” and “temporary disability insurance.” In California, the paid medical leave portion of its program is called “state disability insurance.”

4. Multi-State Employers May Offer Leave When Your State Does Not

There is potential for inequities among PFML benefit entitlements for employees of large companies with operations in several states (i.e., you work in Idaho for a company based in California, and do not have the same state-sponsored leave benefits as your fellow employees). But multi-state employers are working to find ways to level the playing field for all their employees. Adding more company-sponsored leave programs is one answer. And a growing number of states are giving employers access to a PFML benefit they can voluntarily purchase or opt into.

“We have seen a significant increase in the past several years with employers creating their own paid parental and family caregiver leaves which speaks to the need for equity regardless of location,” says Sharon Andrus, head of paid family and medical leave for Group Benefits at The Hartford. “In addition, since the pandemic, employers are also using these policies as retention and recruitment tools.”

One effective strategy for multi-state employers is maintaining short-term disability insurance, also known as short-term income protection benefits, as a benefit staple. When their employees who work in a non-PFML state are out with a covered illness or injury, short-term income protection pays a cash benefit, much like the medical portion of PFML.

However, even states with PFML programs place limits on leave lengths and cash benefit amounts for those PFML programs. Employers are bridging those gaps with short-term income protection benefits, as well.

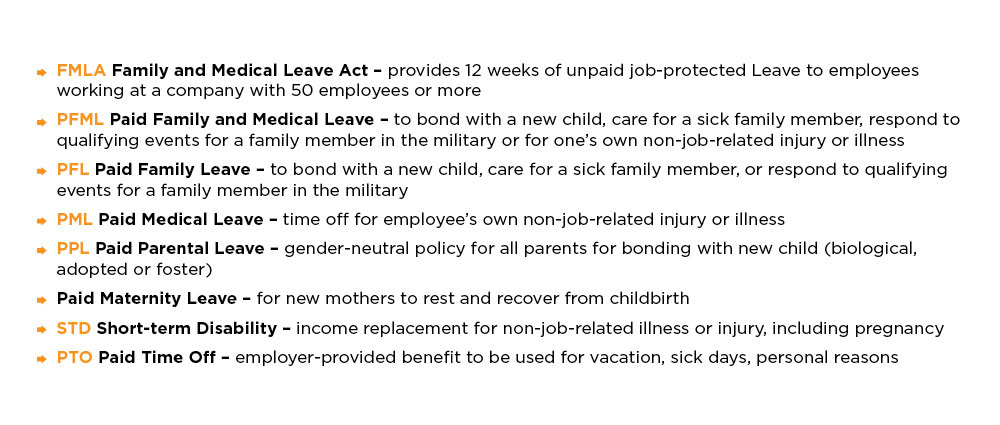

5. PFML Is Not the Only Type of Leave

Employees may be able to tap into many different types of available leaves, both paid and unpaid, when they need extended time off to care for themselves or their family. In addition to PFML, there may be time off through the federal Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA), company paid parental leave, short-term income protection benefits, long-term disability coverage (also known as long-term income protection benefits) and other paid time off. Most PFML programs have a maximum of paid benefits and time off available within a year’s period. Depending on the reasons for the time off, employees could layer many of these leaves to maximize their benefits.

Since the pandemic accelerated the trend for more paid time off, employees now have more options, depending on their needs. In fact, The Hartford’s 2022 Future of Benefits Study found that 81% of employers increased the types of paid time away from work they provide beyond state or federal requirements, an increase from 75% in February 2021.

“The sheer number of different leave types can seem overwhelming at first, especially as employees and employers try to understand each one and how they might complement each other,” says Janice Malcolm-Beeker, assistant general counsel for Group Benefits at The Hartford. “Benefits education is essential to give employees a working knowledge of what’s available to them and how they can best use those leaves.”

6. Who Administers PFML Benefits Depends on Your State

State-mandated PFML programs are generally administered in two ways: through a state-run program or through an employer’s private plan. Nearly all states that require PFML give employers the option to offer the benefit through a private plan as long as the plan meets or exceeds the state benefits. Rhode Island and the District of Columbia are the exceptions. They require employers to use the RI- and DC-run programs rather than use an employer private plan.

A private insurer with experience in managing leaves can help employers integrate PFML with their other leaves. This partnership can also translate into a more streamlined claims and benefits experience for employees.

“The insurance benefits industry actively partners with employers to help support their employees with PFML plans and administrative services that not only meet state requirements, but also the needs and desires of today’s workforce,” Malcolm-Beeker says.

The ability for an employer to partner with the private benefits industry could find its way as one of the building blocks of a potential national PFML program. More on that below.

A world view of where paid leave is available for new mothers. Source: World Policy Analysis Center Report, FMLA Turns 25, 2018

7. COVID-19 Created Temporary Federal Leave Law Changes

More states are adopting PFML programs because there is no national program. The U.S. trails most of the industrialized world on this issue, but the U.S. does have the FMLA that was enacted in 1993.

The federal FMLA allows up to 12 weeks of unpaid job-protected leave. It applies to companies with 50 or more workers and in some instances, FMLA can be taken at the same time as PFML to provide underlying job protection.

The federal government’s response to the pandemic was to make temporary job-protected emergency paid family and sick leave available under the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA). The FFCRA allowed employers to use tax credits to provide short-term paid sick leave and paid childcare leave under the FMLA.1 So, for the first time nationally, paid family and sick leave was accessible – temporarily – for many employees.

8. What Would a National Paid Leave Policy Look Like?

Proponents of a national PFML plan were hoping to build on momentum from the pandemic that highlighted the importance of PFML in an uncertain time. Congress came close in 2021 to passing a national policy, but it ultimately failed. One of the proposals that Congress considered was modeled after several state PFML programs. It would have given most workers 12 weeks of paid time off for family or their own health needs.

Private benefits currently play a role in several state supported PFML programs which allow employers to use a private benefits vendor to administer a company’s PFML plan.

“Private insurers have almost 80 years of experience coordinating state-mandated benefits,” Andrus says. “That’s more important than ever as new leave laws emerge and make administration and compliance more complex for employers.”

A timeline of paid family and medical leave in the U.S. Source: The Hartford’s 2020 PFML Research

9. Three Women Led America’s Leave Movement

The pandemic upended life and work for nearly everyone, but it was particularly difficult for women – still the traditional family caregivers. By January 2021, a total of 2.3 million women left the U.S. workforce since the pandemic began.3 According to the National Women’s Law Center, the women’s labor force participation rate of 57% was the lowest since 1988.4

That brings us back to where all this started.

The roots of the FMLA and PFML sprung from women who advocated – from classroom to courtroom – for their own job security at a time when pregnant women faced job discrimination. School teachers, for example, were often forced to take unpaid maternity leave midway through their pregnancy in order to keep their job when returning after childbirth. The prevailing attitudes were that the pregnancy would be a classroom distraction and that continuing to work would be harmful to the expectant mother.

All that changed in 1974, when a pair of junior high school teachers from Cleveland, Ohio, took on the system. Jo Carol La Fleur and Ann Elizabeth Nelson challenged their school district’s policy, saying it was discriminatory and violated their constitutional rights.5 The teachers pressed their case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, and the Court agreed with them. Four years later, Congress enacted the Pregnancy Discrimination Act, prohibiting employers from discriminating against women due to pregnancy, childbirth or related conditions. But even with the new law, there was still more work to do.

Enter Lillian Garland.

The single mother lost her job at a California bank in 1984 when her employer filled her position while she was out on leave to have her child. She sued the bank, arguing that she was protected by a California state law that gave women up to four months of unpaid disability leave for pregnancy or childbirth. That fight also landed in the nation’s highest court, which ruled in 1987 that the California law was indeed constitutional.6

Although Garland eventually settled with her employer for back pay, she paid a hefty price for her work on behalf of all employed American women. The tough legal battles and lack of income resulted in her child’s father gaining custody of their daughter.

“When you’re trying to accomplish something, you pay a price,” Garland told the Chicago Tribune in 1987. “Losing custody was my price, a very high price.”

Six years later, the FMLA became the law of the land.

1 Families First Coronavirus Response Act: Employer Paid Leave Requirements

2 Monthly workplace absenteeism was 1.2 million in decade before COVID-19 and 2.5 million in 2020, Source: U.S. Census Bureau on behalf of Bureau of Labor Statistics, Currently Population Survey 2021

3,4 National Women’s Law Center, February 2021 Fact Sheet

5 Cleveland Board of Education v. Lafleur 414 U.S. 632 (1974), Encyclopedia of the American Constitution, August 19, 2019

6 Court Upholds Pregnancy Leave Laws, The Washington Post, January 14, 1987

Information and links from this article are provided for your convenience only. Neither references to third parties, nor the provision of any link imply an endorsement or association between The Hartford and the third party or non-Hartford site, respectively. The Hartford is not responsible for and makes no representation or warranty regarding the contents, completeness, accuracy or security of any material within this article or on such sites. Your use of information and access to such non-Hartford sites is at your own risk. You should always consult a professional.

The Hartford Financial Services Group, Inc. (NYSE: HIG) operates through its subsidiaries, under the brand name, The Hartford, and is headquartered in Hartford, Connecticut. For additional details, please read The Hartford’s legal notice at www.thehartford.com.